Highlights :

- The world is moving rapidly to build solar on agricultural lands, to compliment farming. India needs to learn too.

- Agrivoltaics have the potential to achieve multiple objectives, if done right.

It is a truism that no change is really big enough to matter, unless it impacts the agricultural sector in India. After all, even after 2021, the Agriculture and allied sectors account for over 50% of our workforce, and contribute a substantial 18% to the country’s GDP. With the highest amount of arable land in the world after the United States (US), India has almost 60% of its land under cultivation, to both meet the demands of its large population and serve global markets in many product categories.

Not surprisingly, the sector has a heavy-handed government presence, both benign and counterproductive at times. Without getting into the rest, consider just the power subsidies, where agriculture accounts for 75% of total subsidies, according to a 2020 study by the IISD and CEEW. That is 75% of $25 billion, or Rs 185,000 crores, the sum of direct and indirect subsidies estimated by the same study.

In the same vein, without significant changes in agriculture, all the key commitments made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the COP26 meet in Glasgow, will be that much more difficult to achieve. To recount, besides its net zero by 2070 pledge, India has promised to

- Bring its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030

- Bring its economy’s carbon intensity down to 45 per cent by 2030

- Fulfil 50 per cent of its energy requirement through renewable energy by 2030

- Reduce by 1 billion tonnes, carbon emissions from the total projected emissions by 2030

So why is agriculture critical?

Because all this has to be achieved even as India is committed to a major expansion of its manufacturing base, an energy intensive and carbon intensive process. That makes these targets that much more daunting.

Enter Agrivoltaics

Even as India crossed the 100 GW milestone for Renewable energy (Solar+Wind) capacity last year, the new targets call for adding a further 400 GW by 2030. If you consider the challenges faced in the 100 GW journey so far, you will realise that the case for Agrivoltaics, or the simultaneous use of solar on land used for crops too, will only get more compelling with time.

Agrivoltaics offer the kind of solutions policy makers would normally dream of. A direct attack on unsustainable power subsidies, new income avenues for farmers, and at a higher level, helping meet our Renewable energy goals and reducing agricultural carbon emissions. Why do we believe the time is close? Let’s look at some domestic inputs first.

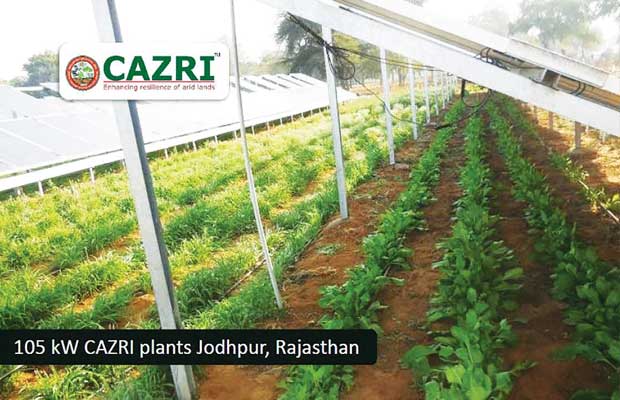

A research paper on “Agrivoltaic system to enhance land productivity and income” by Dr. Priyabrata Santra, Principal Scientist at Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR)-Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, looked at the increasing energy demands for Indian agriculture as mechanisation and other changes take hold. He estimated that energy use in agriculture needs to be increased from 1.6 to 2.5 kW/ ha to meet the production target for the next 20 years. How then can the spiral[1]ling demand for energy and food be met in a way that sustains and promotes both sectors?

Dr.Santra believes that agrivoltaics, or agri-PV can play a significant role.

As a production-oriented sector, agriculture requires energy as an important input to ensure efficiency for production. As per industry estimates, the total energy consumption of the agricultural sector in India is close to eight percent. Pumping of irrigation water, use of machinery for various farm operations, processing, and value addition for farm products, are some activities which drive consumption of energy usage up by agriculture.

Besides this, agriculture also contributes significantly to greenhouse emissions. A report prepared by a team of researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre in the United Kingdom states that India has the potential to cut 18% of its annual greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and livestock. “The reduction potential represents 85.5 mega (million) tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year.” Hence the case for agrivoltaics that could allow India to reduce GHG by agriculture, while maintaining food productivity.

Potential and Scope of Agri-voltaics in India

A strong advocate of agrivoltaics in India, Principal Scientist at ICAR, Dr Priyabrata Santra says, “India needs to combine two important missions of the country – the Food Security and Solar mission by applying agrivoltiacs to multiply land productivity.”

He adds, “Agrivoltaics concept started in India because renewable energy (RE) and ground-based PV installation required land. Land being a scarce commodity, there is a certain amount of competition for it between the RE and the infrastructure sectors.” We cannot increase the RE capacity at the cost of agriculture production or by affecting the agricultural community, he adds.

Ongoing Research On Agrivoltaics Here

“There is a need to make a compromise between RE and agriculture as both are competing for land. So, Agrivoltaics in that sense provides a win-win for both sectors”

Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO of National Solar Energy Federation of India (NSEFI) agrees. Pulipaka says, “India is predominantly an agrarian economy, and it would make a lot of sense to co-locate solar and agriculture. This also gives us an opportunity to align Government goals of achieving 175 GW by 2022, with other farmer centric goals that involve doubling of farmer income.”

Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO, NSEFI

Pulipaka adds, “Even if we put one percent of arable land to agri-PV, it will be around 180-182 GW and that’s huge potential for India.”

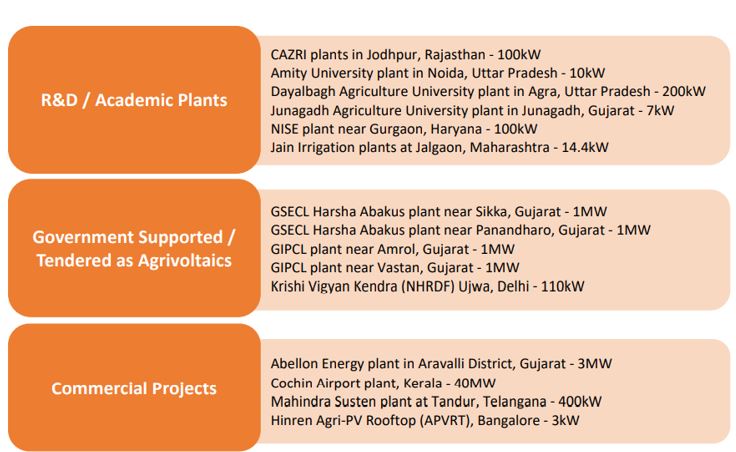

Pulipaka’s NSEFI in association with IGEF (Indo-German Energy Forum) in its 2020 report on Agrivoltaics in India (Overview of Operational Projects and relevant Policies) had highlighted that co-location of solar panel and commercial crops is a feasible solution in the Indian context. However it has not yet been fully explored. It also shared that the capacity of the agrivoltaic installations in India ranges between 3kWp and 3MWp. Utility-scale agrivoltaic projects of more than 3MWp have not yet been deployed. As a result, there are no experiences of respective technical, economic and agricultural viability.

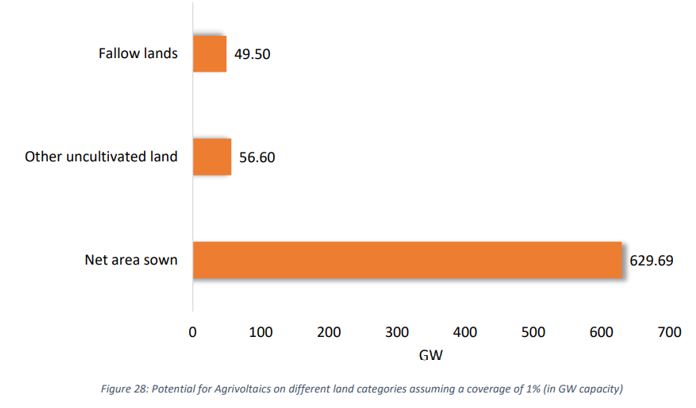

The report had stated that “Estimating the potential of agrivoltaics in the country, a safe place to begin with is what if 1% of each of the land under agriculture, barren land and other uncultivated land is used for agrivoltaics with 5.5 acres of the land suitable for 1 MW of agrivoltaics, a total potential of 629.69 GW alone is realised from net area sown (agricultural) lands. The potential of Agrivoltaics is 49.50 GW and 56.6 GW for fallow lands and other uncultivated lands, respectively.

How Agrivoltaics Can Contribute

For India’s farmers transitioning from a hardcore non-digitised agriculture to a more digitised economy, the shift could be decisive. Pulipaka explains that India will witness a paradigm shift in the way agriculture is perceived. And when that happens, electricity will also be part of this transition. “If we are able to figure out the way forward thoughtfully, in 5-10 yrs it is completely possible to make the farming sector completely independent from fossil fuel generation.”

An Independent Researcher and author of the recent report by Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) on ‘Agrivoltaics: How India can combine solar power and farmland’ Dr. Charles Worringham agrees on the fit between agrivoltaics and India’s energy needs, with a caveat.

Charles adds that India needs to create a knowledge base about what works, which crops perform better than others, and many other related details. There are a number of research initiatives taking place, and such a knowledge base will help bring the best use cases out in a rational way.

In India, as per the NSEFI-IGEF report, close to half of the plants are in Gujarat, a state which has been credited as the first state in the country to examine Agrivoltaics as a concept on a broader scale. Industry experts say that India must push its ‘least solarised’ states also to utilise agrivoltaics to improve land productivity as well as farming sector income.

BOX: Agrivoltaics: A reality or a dream?

Rajesh Kumar, a 30-year old farmer started his own agro-voltaic project in Mandi District of Himachal Pradesh. With a total plant capacity of 250kw AC, spread over two acres of area under cultivation. “While remaining a farmer at the core, I wanted to try entrepreneurship,” says Kumar. “Agri-PV looked like an attractive opportunity to combine agriculture with solar.

He heard about the agri-PV project from an independent NGO Agrivoltaics Services run by Vikas Sharma, working to promote and encourage farmers to utilise the opportunity agrivoltaics offers.

Kumar says, “I was impressed and wanted to see what benefits I can draw from it.” With the support of Sharma, I started the project.” Initially, our experiment with rice and wheat crops did not work, but now we are successfully growing crops like cabbage, eggplant, onion, garlic, chili and among others.

Kumar started the Mandi project in 2018, under PM KUSUM Scheme’s component A, at a total installation cost of Rs 1 Cr (including non-AC warehouse). Through the agrivoltaics experiment on his farmland, Kumar generated total power of around 3,25,000kwh, which for him means an income of close to 13 lakh annually at the rate of 3.98 per unit.

Vikas Sharma points out that financial funding to lower income farmers is also very important, to encourage them to take up agri-PV.

Another interesting case is of a family in a village called Bhaloji of Rajasthan. The Yadava family set up its first farm-based solar plant on its farming land. This one MW solar plant was also set up under the PM KUSUM scheme. Set up on a semi-arid 3.5 acre farmland near Kotputli town, this agri-PV project is a classic example of how an agrivoltaic project should take off.

The Yadava family who owns the farmland entered into a contract with the Rajasthan Renewable Energy Corporation Ltd for 25 years. And now, as reported, the project yields an income of over Rs 4 lakh per month. The Yadava family had started with a 11-KW plant at an initial cost of Rs 2.5 lakh. For the people of this state which holds large patches of uncultivable land, this project speaks volume of the profitability agrivoltaics can offer to the farmers.

In September of 2020, the Yadavas signed another contract with the Central government to produce solar energy under the scheme. The project now has the capacity to produce 17 lakh units of electricity per year. The project has been developed at a cost of Rs 3.70 crore and is expected to generate an annual income of about Rs 50 lakh for the Yadava family from the purchase of electricity by discoms at Rs 3.40 per unit.

The total installed agrivoltaics projects stands at 16 today across the country. But some of the bigger ones may come up in 2022. Gro Solar Energy, a Maharashtra based company has already been commissioned for a 7MW AC Solar Energy Project at Degaon in Sindakhede Tahsil of Dhule District of Maharashtra.

This, so far, would be the biggest agrivoltaics project in India. The Project has been taken up under the Govt. of Maharashtra’s Mukhyamantri Saur Krishi Vahini Yojana. The scheme has the objective of providing daytime power to the farmers. The project is connected at 11kv level which supplies the solar energy to farmers through Agriculture feeder lines. The PPA is with Mahagenco, the Govt. of Maharashtra’s power generation utility, with a back to back PSA with State’s distribution utility, Mahadiscom.

Dr Gulabsing Girase, Director, Gro Solar Energy Pvt Ltd says, “We have designed the plant a little differently to accommodate solar plus agriculture. However, we have just initiated the agricultural activities and it will take about a year to see the results.”

The oldest of these sites was commissioned by Abellon Energy in 2012 with agrispecialist Jain Irrigation Systems Limited (JISL) from the state of Maharashtra. The NSEFI report classifies the various agrivoltaic projects in the country in three different types – one with R&D focus, government supported projects and commercial projects developed by private entities.

Opportunities and Challenges

Interestingly, across the world, combining food production with solar energy has yielded ground breaking results. The global market estimates of agrivoltaic installed capacity have grown from about 5 MW in 2012 to approximately 2.9 GW today. This is led mostly by Germany, France, and Italy. The Covid recovery plan of these countries devotes over 1 billion Euros towards establishing 2GW of agrivoltaic projects.

While agrivoltaics may not be the panacea for all challenges the farming sector and farmers face in India, but it does hold potential in how farmer interests are ‘perceived, prioritised and enhanced’. The government seemed to understand this, when it launched the PM KUSUM scheme/s.

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha Evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) was started in 2019. The idea was to give farmers greater financial security as well as more sustainable water access by generating solar power on their farms.

The scheme is divided into three key components. Under the Component A, the aim has been to install grid connected ground mounted solar power plants (upto 2 MW) aggregating to a total capacity of 10 GW. Component B expects installation of two million standalone solar pumps, while component C is intended to solarize 1.5 million grid connected agricultural pumps. Even as generous budgetary support has been provided for, progress on the ground has been slow, due to Covid, and red tapism.

An IEEFA analysis in June 2021 says that out of India’s mission to deploy 2 million off-grid solar-powered irrigation pumps, only one-eighth of the target has been achieved. The report urged the central and state governments to remove bottlenecks in the installation of solar pumps. “The scheme should have accelerated solar pump deployment, but at the end of financial year 2019/20 a total of around 246,000 solar pumps were deployed and only 8,900 of these were installed in the 12 months after the scheme was launched in 2019,” the report stated.

Even as solar pumps are finally moving faster, a thrust on component A, or ground mounted solar connected to the grid, is being made now. In just the past year, over 4.7 GW of projects under component A have been sanctioned by MNRE, with little to show on the ground yet.

Santra explains “Currently, India’s total installed capacity is about 48 MW as per the recently published report of National Solar Energy Federation of India (NSEFI).”

He cautions though that, certain bottlenecks have to be removed. “So, it is extremely important that farmers are provided an enabling environment, selling opportunities. Then DISCOMs too play a critical role.”

Santra explains that with farmers increasingly impacted by the climate crisis in the form of erratic weather patterns which have made farm income more uncertain.

“Agrivoltaics give farmers an assured income, as it helps them generate electricity and also to sell to the DISCOM,” he adds.

Of the total farmer population in India, 85% are marginal and small land holding farmers with less than two hectares of land. Santra says that they do not have capacities to invest and install in the required solar systems. Another challenge is that if there are no electricity grids in the vicinity, the opportunity to sell excess electricity is lost.

Availability of DISCOMs to purchase electricity is essential. At the moment, DISCOMs are not fully able to purchase electricity from agrivoltaics, due to lack of ‘demand’ as well as contracts with coal-based operators. Thirdly, solar workers on ground (developers, companies) will also play a key role.

Santra stresses that all three solar functionaries, i.e. agriculture community, RE sector and DISCOMs need to work together to include marginal farmers in the solar push.

Pulipaka says, “The PM Kusum scheme has come at the right time. If you look at component A, especially 500 kW, it is a perfect solution, but we must also be mindful of the fact that solar spread is equally as important as solar growth.” We need to ensure that the distributed part under the component A is well-nourished, he adds.

What also has to be kept in mind is the fact that while we work out issues like land lease rate, component of particular percentage of electricity tariff that farmers get per unit through innovative business models, we must not forget that land ownership has to remain with the farmers, asserts Pulipaka. “Rights of the farmland must always be with the farmers” and “agrivoltaics needs be implemented only with support of the farmers.”

While endorsing Pulipaka’s views, Charles adds another perspective that the question of land classification must also be tackled soon. “In most cases solar on farmland requires conversion of farmland into commercial land, and that discharges it from enjoying the benefits of being an agricultural land.”

This could mean loss of various benefits by the farmer, while allowing COVER STORY the farmers to fall at the mercy of energy developers, he adds. “This defeats the very purpose of agrivoltaics.”

Dr Girase asks for a policy framework for agrivoltaics projects in India. “Some norms, some differential tariffs and eligibility criteria defining who could set the agrivoltaic project needs to be there”. “In MNRE documents, if one goes through you can bid only if you have a particular amount of turnover, and have a very well established business.”

Clarity is also required to throw light on how revenue that you earn from agrivoltaics will be treated by tax authorities for that matter, Girase adds.

Pulipaka concurs, adding that PM KUSUM has tackled the issue of land conversion at least.

Firming up a roadmap

As a part of recommendations, NSEFI in its report had stated that there is a need for the Government to define specific targets for agrivoltaic plants in India with a year wise trajectory for the next 10 years.

NSEFI recommends that the Government may prefer to start with a modest target of 20-30 MW in the first year and accelerate it in the next 10 years, to garget 15 GW by 2030.

Charles too adds that while it may be relatively easier to build a very high capacity solar park in the sunny part of Rajasthan but evacuating that energy and getting it into the grid where load centers are there still requires massive infrastructure spending, in order to ensure appropriate transmission capacity is in place. He also adds that “We have to recognise the fact that challenges facing the farming sector in India are broad ranging and significant. India needs to move towards a position in which farmers can get benefits from generating power and not subsidizing power.

And this may not be possible with one set of guidelines for the entire country simply because of different types of soil, rain cycle, irrigation situations, and access to markets. Charles in his IEEFA report had also stated that the biggest roadblock is the fact that, currently the sector’s growth is limited by uncertainties stemming from the separation of responsibilities between state ministries of agriculture and energy. This is reflected at the central level with its Ministries of New and Renewable Energy on the one hand, and Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare on the other.